Integration Test Isolation in a Next.js App with Drizzle ORM

1. Introduction: The Complexity of Modern Integration Testing

The evolution of web application architecture has precipitously increased the complexity of ensuring software quality. In the era of the monolithic, server-rendered application—typified by frameworks such as Ruby on Rails or early ASP.NET—testing strategies were relatively straightforward. The application ran in a single process, connected to a single relational database, and served HTML directly. Integration testing in such an environment was a solved problem: wrap the test in a database transaction, execute the logic, and roll back the transaction at the end of the test. This approach, often referred to as the “transactional rollback” strategy, provided a clean slate for every test case, ensuring isolation and determinism with minimal overhead.

However, the modern full-stack landscape, dominated by React meta-frameworks like Next.js and diverse data-access layers such as Drizzle ORM, has fundamentally altered this equation. The shift towards serverless compute models, the introduction of React Server Components (RSC), and the decoupling of the frontend from the backend logic via mechanisms like Server Actions have introduced new boundaries and constraints. In this environment, the database is no longer just a passive store of state; it is a shared mutable resource accessed by highly concurrent, asynchronous processes that may not share the same memory space or execution context as the test runner.

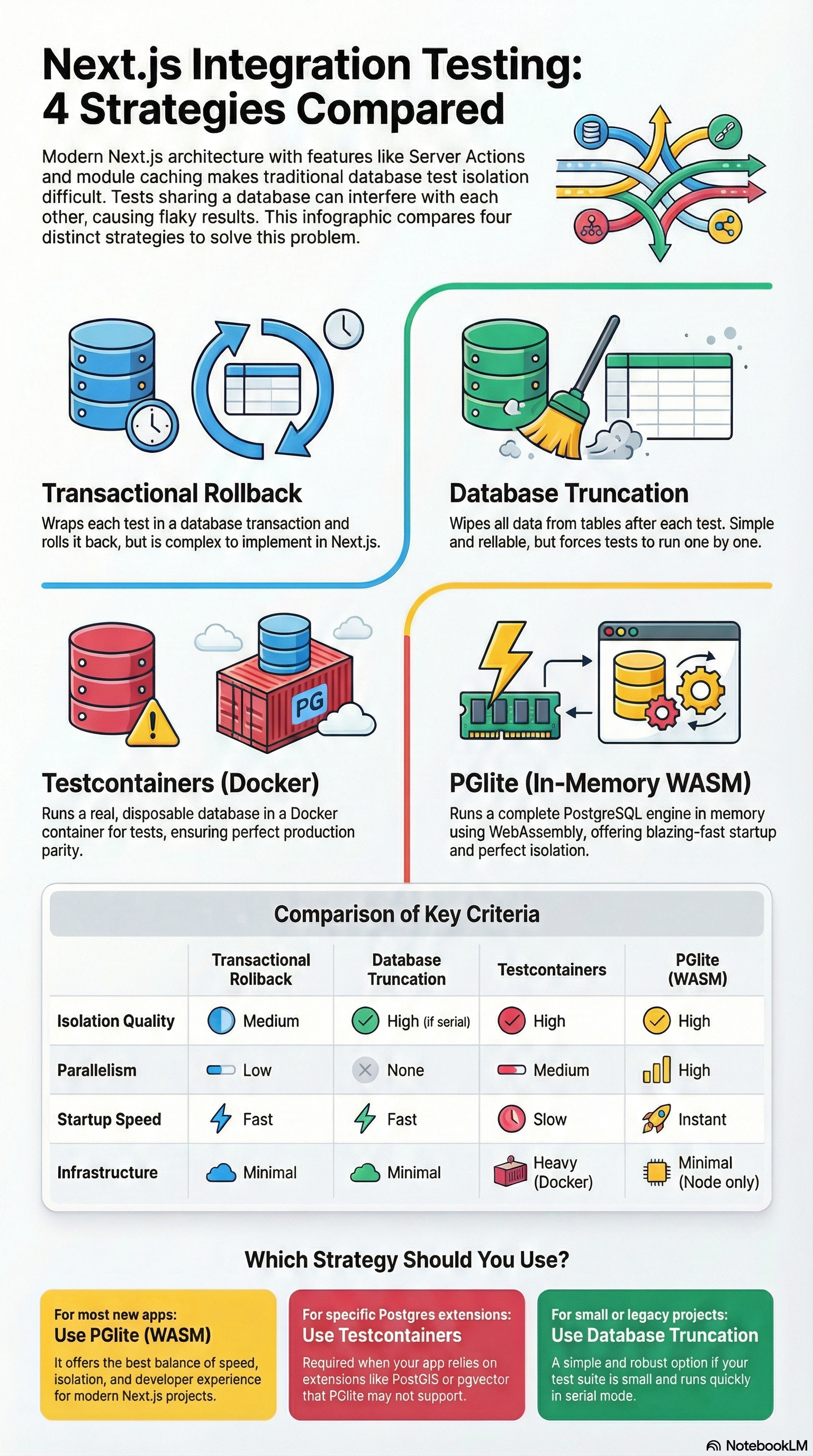

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the strategies available for achieving rigorous integration test isolation in a Next.js application using Drizzle ORM. It explores the theoretical underpinnings of database isolation, the specific architectural challenges posed by the Next.js App Router, and the practical implementation of four distinct testing methodologies: Transactional Rollbacks, Database Truncation, Containerised Isolation (Testcontainers), and In-Memory WebAssembly Databases (PGlite). By examining the mechanisms, performance characteristics, and trade-offs of each approach, this document aims to equip engineering teams with the knowledge required to architect robust, scalable, and non-flaky test suites for mission-critical applications.

1.1 The Imperative of Isolation

Integration testing sits at the precarious intersection of the testing pyramid. Unlike unit tests, which verify discrete logic in isolation by mocking external dependencies, integration tests must validate the interaction between the application code and its infrastructure—specifically, the database. The fidelity of these tests is paramount. If a test mocks the database driver, it ceases to be an integration test; it merely tests the developer’s assumptions about how the database should behave, rather than how it actually behaves.

The central challenge in integration testing is Shared Mutable State. When a test suite runs, multiple test cases execute against the database. If these tests are not perfectly isolated, they interfere with one another, leading to a class of failures known as “flaky tests.” Flakiness manifests in several ways:

- Data Pollution: One test inserts a record (e.g., a user with email

test@example.com) that persists after the test finishes. A subsequent test, expecting an empty user table or attempting to create a user with the same unique email, fails. - Phantom Reads: In a concurrent test environment, a query in Test A might inadvertently retrieve data inserted by Test B, leading to assertion failures that are impossible to reproduce when running the test in isolation.

- Race Conditions: Tests that modify global configuration or shared singleton resources can create non-deterministic outcomes based on the precise timing of execution by the CPU scheduler.

To mitigate these risks, the testing environment must guarantee that every test runs in a pristine environment. The database state at the beginning of a test must be known, deterministic, and unaffected by any previous or concurrent test execution.

1.2 The “Next.js Effect”: Architectural Constraints

Next.js, particularly with its App Router architecture introduced in version 13, imposes specific constraints that complicate traditional isolation strategies.

-

Server Actions as Remote Procedure Calls (RPC): Server Actions in Next.js allows functions to be executed on the server, triggered directly from client-side components. From a testing perspective, these are not simple function calls; they are asynchronous operations that often run in a separate context. Testing them requires an environment that can simulate the Next.js server runtime, including access to environment variables, headers, and cookies.

-

The Singleton Pattern & Module Caching: In a typical Next.js application, the database client (Drizzle instance) is instantiated as a global singleton. This is necessary to prevent connection exhaustion during development (hot reloading) and to manage connection pooling in production. However, this global singleton makes Dependency Injection (DI)—a primary technique for test isolation—significantly more difficult. If a Server Action imports the database client directly from a static module path (e.g.,

import { db } from '@/db'), the test runner must intervene at the module loading level to inject a test-specific database instance. -

Server-Only Boundaries: Next.js enforces strict boundaries between server and client code using the

server-onlypackage. Integration tests that import server-side logic must execute in a Node.js-compatible environment (like vitest with a node environment) rather than a browser-like environment (like jsdom), or they will trigger build-time errors. This constrains the choice of test runners and mocking strategies.

1.3 Drizzle ORM: A TypeScript-First Approach

Drizzle ORM represents a modern approach to database interaction, favoring type safety and SQL-like syntax over the heavy abstraction layers of traditional ORMs. It separates the query builder (the TypeScript API) from the driver (the mechanism that talks to the database). This separation is crucial for testing because it allows the underlying driver to be swapped—for example, replacing a network-based Postgres client with an in-memory PGlite client—without changing the application logic. However, Drizzle’s reliance on specific driver features (like prepared statements or specific transaction APIs) means that the test environment must closely mirror the production environment’s capabilities to avoid false positives.

2. Theoretical Framework: ACID Properties and Test Concurrency

To understand why integration test isolation is difficult, one must delve into the fundamental properties of relational databases: ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability). Integration testing strategies essentially manipulate these properties to achieve their goals.

2.1 Atomicity and Test Boundaries

Atomicity guarantees that a transaction is treated as a single “unit of work,” which either completely succeeds or completely fails. The Transactional Rollback strategy leverages this property. By wrapping a test case in a transaction, the test runner ensures that all database writes are provisional. When the test concludes, the runner issues a ROLLBACK command, which atomically undoes all changes. This relies on the database’s Write-Ahead Log (WAL) to revert the state efficiently, without the overhead of deleting records from the disk.

However, Atomicity interacts complexly with modern application logic. If the application code under test itself uses transactions (e.g., a signup flow that creates a user and an organisation in a single transaction), the test runner must support Nested Transactions. In PostgreSQL, true nested transactions do not exist; they are simulated using SAVEPOINT. Drizzle ORM supports this via its tx API, allowing a test to start a transaction (Level 1) and the application to start a nested transaction (Level 2). A rollback of Level 2 reverts to the savepoint, while a rollback of Level 1 reverts everything.

2.2 Database Isolation Levels

The “I” in ACID refers to Isolation—the degree to which a transaction is protected from the effects of other concurrent transactions. PostgreSQL offers several isolation levels:

- Read Committed (Default): A query sees only data committed before the query began.

- Repeatable Read: A query sees a snapshot of the database as of the start of the transaction.

- Serialisable: The strictest level, ensuring that the result of concurrent transactions is the same as if they had executed serially.

For integration tests running in parallel against a shared database, Read Committed is often insufficient. If Test A (running in a transaction) inserts a record, and Test B (also in a transaction) runs a query that counts records, Test B generally won’t see Test A’s uncommitted data. However, if Test A commits (which might happen if the application logic forces a commit), Test B’s state is polluted. This creates a “race condition” where tests pass or fail depending on which one finishes first. Achieving true isolation usually requires ensuring that tests running in parallel never share the same database instance, or use strict row-level locking which degrades performance.

2.3 The Throughput vs. Latency Trade-off in Testing

Architecting a test suite involves a fundamental trade-off between Latency (how fast a single test runs) and Throughput (how fast the entire suite runs).

-

Serial Execution: Running tests one by one (latency focused) is the easiest way to ensure isolation. You can use a single database and truncate it between tests. However, as the suite grows to thousands of tests, the total execution time (throughput) becomes unacceptable, leading to slow CI pipelines.

-

Parallel Execution: Running tests concurrently (throughput focused) drastically reduces total time but requires advanced isolation strategies. Each parallel worker needs its own isolated environment (e.g., its own database schema or container) to prevent collisions. This increases the resource cost (CPU/RAM) of the test runner.

The following sections analyze four strategies that navigate this trade-off space differently.

3. Strategy I: Transactional Rollbacks (The “Rails” Pattern)

The Transactional Rollback strategy is often considered the “gold standard” in frameworks like Ruby on Rails and Django. It promises the best of both worlds: speed (no need to recreate schemas) and isolation (changes are never committed).

3.1 Mechanism of Action

In this model, the test runner performs the following sequence for each test case:

- Connect: Establish a connection to the database.

- Begin: Execute

BEGINto start a transaction. - Run: Execute the test logic. The application performs

INSERT,UPDATE, andDELETEoperations. These changes are visible to the connection but not to the outside world. - Rollback: Execute

ROLLBACKin the teardown orafterEachhook. The database discards the changes.

This approach is highly efficient because ROLLBACK is an inexpensive operation for the database engine compared to TRUNCATE or DELETE, which require scanning tables and updating indexes.

3.2 Implementation Challenges in Next.js

While conceptually simple, implementing this in a Next.js/Drizzle application is fraught with architectural difficulties, primarily due to the Connection Context Problem.

In a typical Next.js app, the database client is a global singleton imported by Server Actions:

// src/lib/db.ts

export const db = drizzle(postgres(process.env.DATABASE_URL));

When a test runs, it typically initiates a transaction on its own connection instance. However, when the test calls a Server Action, that action imports the global db instance, which usually maintains its own connection pool. Consequently, the Server Action executes its queries outside the test’s transaction. The changes are committed to the database, polluting the state for subsequent tests and rendering the ROLLBACK ineffective.

3.3 The Proxy & AsyncLocalStorage Solution

To make Transactional Rollbacks work in Node.js/Next.js, one must force the application code to use the test’s transaction connection instead of the global pool. This requires a form of “Context Propagation.”

AsyncLocalStorage (ALS) from the node:async_hooks module provides a mechanism to store data that is unique to the current asynchronous execution context (similar to Thread-Local Storage in multi-threaded languages).

Implementation Architecture:

The Wrapper: Create a database accessor that checks the ALS store.

import { AsyncLocalStorage } from 'node:async_hooks';

export const txStorage = new AsyncLocalStorage<any>();

export const getDb = () => {

const tx = txStorage.getStore();

return tx ? tx : globalDb;

};

The Test Hook: In beforeEach, start a transaction and enter the ALS context.

test('example test', async () => {

await globalDb.transaction(async (tx) => {

await txStorage.run(tx, async () => {

// Inside this block, getDb() returns 'tx'

await myServerAction();

tx.rollback(); // Force rollback at end

});

});

});

Refactoring: The application must be refactored to use getDb() instead of importing db directly, or the db export must be a Proxy object that handles this logic internally.

3.4 Pros and Cons

| Feature | Analysis |

|---|---|

| Speed | High. Rollbacks are nearly instantaneous. No file I/O or schema rebuilding is required between tests. |

| Parallelism | Low/Complex. Since multiple tests effectively share the same underlying database instance (even if wrapped in transactions), running them in parallel requires careful management of connection limits and locking. It essentially forces serial execution within a single database. |

| Complexity | High. Requires invasive changes to the application architecture (using ALS or Proxies) or strict Dependency Injection. Testing “transactional” logic within the app becomes confusing (nesting transactions inside test transactions). |

| Fidelity | Medium. Logic that relies on “after commit” hooks or side effects visible to other connections cannot be tested easily because the transaction is never actually committed. |

Verdict: While powerful, the Transactional Rollback strategy fights against the grain of the Next.js App Router’s module system. It is best suited for applications that already use heavy Dependency Injection patterns (like NestJS) rather than standard Next.js patterns.

4. Strategy II: Database Truncation (The “Clean Slate” Approach)

The Truncation strategy is the brute-force alternative to rollbacks. Instead of preventing writes from persisting, we allow them to persist and then aggressively clean the database after every test.

4.1 Mechanism of Action

- Global Setup: A real database is spun up (usually via Docker) and the schema is migrated once at the start of the test suite run.

- Test Execution: The test runs against this real database. Data is committed.

- Teardown (

afterEach): A utility function queries the database for all table names and executesTRUNCATEcommands to wipe all rows.

4.2 Handling Foreign Keys and Sequences

A naive DELETE FROM table is insufficient and slow. TRUNCATE is faster as it deallocates data pages. However, relational integrity constraints (Foreign Keys) pose a challenge. You cannot truncate the users table if the posts table references it.

To solve this, PostgreSQL provides the CASCADE option:

TRUNCATE TABLE users, posts, comments CASCADE;

Additionally, TRUNCATE does not reset auto-incrementing primary keys (IDENTITY columns) by default. If Test A creates User ID 1, Test B will create User ID 2. If Test B asserts “User ID should be 1”, it will fail. The RESTART IDENTITY clause is required.

Optimised Drizzle Implementation:

import { sql } from 'drizzle-orm';

export async function resetDatabase(db: any) {

// Disable triggers if necessary or use CASCADE

const query = sql<string>`

SELECT table_name

FROM information_schema.tables

WHERE table_schema = 'public' AND table_type = 'BASE TABLE'

`;

const tables = await db.execute(query);

if (tables.rows.length === 0) return;

// Construct a single query to truncate all tables at once

const tableNames = tables.rows.map((row: any) => `"${row.table_name}"`).join(', ');

// RESTART IDENTITY resets sequences

// CASCADE handles foreign keys

await db.execute(sql.raw(`TRUNCATE TABLE ${tableNames} RESTART IDENTITY CASCADE`));

}

This script is robust because it dynamically discovers tables, ensuring that newly added tables are automatically cleaned up without updating the test helper.

4.3 The Concurrency Bottleneck

The fatal flaw of the Truncation strategy is its incompatibility with parallel testing. Since there is only one shared database instance, you cannot run Test A and Test B simultaneously. If Test A truncates the database while Test B is in the middle of an operation, Test B will fail catastrophically.

This forces the test runner (e.g., Vitest or Jest) to run in Serial Mode (--runInBand or maxWorkers=1). As the application grows to hundreds of integration tests, the feedback loop extends from seconds to minutes, severely hampering developer productivity.

4.4 Pros and Cons

| Feature | Analysis |

|---|---|

| Speed (Per Test) | Medium. Truncate is faster than DROP/CREATE but slower than ROLLBACK. The database must physically clean pages on disk. |

| Speed (Total) | Low. Forces serial execution. Scalability is linear with the number of tests. |

| Simplicity | High. Very easy to understand and implement. No “magic” proxies or complex context switching. The database behaves exactly as production. |

| Reliability | High. Cleans everything. Less prone to subtle state leaks than complex transaction nesting. |

Verdict: Database Truncation is a viable strategy for smaller projects or CI pipelines where parallelism is not a priority. It is robust and simple but hits a hard ceiling on scalability.

5. Strategy III: Containerised Isolation (Testcontainers)

To solve the concurrency problem of the Truncation strategy without sacrificing the fidelity of a real database, many teams turn to Testcontainers. This library allows the test runner to programmatically spin up disposable Docker containers for dependencies.

5.1 The Architecture of Ephemeral Infrastructure

Testcontainers for Node.js wraps the Docker API. It allows a test to:

- Request a PostgreSQL image (e.g.,

postgres:16-alpine). - Start the container on a random, available port.

- Wait for the database to be ready (using log strategies or health checks).

- Return the connection string to the application.

- Destroy the container automatically when the test finishes.

The “Ryuk” sidecar container is a special component of Testcontainers that ensures cleanup. It monitors the connection to the test runner; if the runner process dies (even unexpectedly), Ryuk kills the spawned containers, preventing “zombie” processes from consuming system resources.

5.2 Implementation Modes

There are two ways to deploy this for Next.js testing:

5.2.1 Singleton Container with Logical Isolation

Spinning up a Docker container takes time (500ms - 2s). Doing this for every test file is often too slow. A common pattern is to start one container for the entire test suite (global setup). Then, for each test worker, create a unique logical database inside that container.

- Setup: Container starts at port 5432.

- Worker 1: Connects, runs

CREATE DATABASE test_db_1, migrates, runs tests. - Worker 2: Connects, runs

CREATE DATABASE test_db_2, migrates, runs tests.

This allows parallelism. However, it requires complex orchestration code to manage unique database names and ensure migrations are run for every new logical database created.

5.2.2 Container Per Test File

The most isolated approach is to give every test file its own container.

- Pros: Perfect isolation. No shared state.

- Cons: Heavy Resource Usage. Running 10 parallel test files means running 10 PostgreSQL containers simultaneously. This requires significant RAM and CPU. On a typical CI agent (with 2 vCPUs and 4GB RAM), this will likely cause crashes or extreme slowness due to context switching.

5.3 Drizzle Integration

Connecting Drizzle to a Testcontainer is straightforward since Drizzle accepts any standard connection string.

import { PostgreSqlContainer } from "@testcontainers/postgresql";

import { drizzle } from "drizzle-orm/node-postgres";

// In global setup

const container = await new PostgreSqlContainer("postgres:16").start();

const client = new Client({ connectionString: container.getConnectionUri() });

await client.connect();

export const db = drizzle(client);

5.4 Pros and Cons

| Feature | Analysis |

|---|---|

| Fidelity | Maximum. You are testing against the exact binary version used in production. Extensions (PostGIS, pgvector) work perfectly. |

| Isolation | High. Containers provide process-level isolation. |

| Performance | Low to Medium. Docker startup overhead is the main bottleneck. High resource consumption limits the degree of parallelism possible on standard hardware. |

| Infrastructure | Complex. Requires a Docker daemon availability. This can be challenging in certain CI environments (e.g., Docker-in-Docker setups) or restricted corporate laptops. |

Verdict: Testcontainers is the industry standard for End-to-End (E2E) tests where accuracy is more important than speed. For integration tests that run frequently (e.g., on every file save), it is often too heavy.

6. Strategy IV: In-Memory WebAssembly Databases (PGlite)

The most recent and transformative development in this space is the emergence of PGlite. This technology fundamentally shifts the “Latency vs. Throughput” curve by offering the isolation of containers with the speed of in-memory execution.

6.1 What is PGlite?

PGlite is a build of PostgreSQL compiled to WebAssembly (WASM). Unlike mocks (which fake the database) or SQLite (which is a different database entirely), PGlite runs the actual Postgres query engine code. It executes within the Node.js process memory. It does not require a daemon, a network port, or Docker.

Because it is just a JavaScript object consuming memory, starting a PGlite instance takes milliseconds (~10-50ms), compared to seconds for a Docker container.

6.2 Architecture for Massive Parallelism

PGlite enables a “Database per Test File” architecture without the resource penalty of Docker.

Integration with Vitest:

Vitest is a modern test runner that supports multi-threading. By combining Vitest’s parallelism with PGlite, we can achieve perfect isolation.

- Vitest Config: Configure the test pool to use threads or forks. This ensures each test file runs in its own worker.

- Mocking the Database: We use Vitest’s

vi.mockto intercept imports to the application’s database module. - Setup File: In the setup for each test file, we instantiate a new PGlite database.

// vitest.setup.ts

import { vi } from 'vitest';

import { PGlite } from '@electric-sql/pglite';

import { drizzle } from 'drizzle-orm/pglite';

import { migrate } from 'drizzle-orm/pglite/migrator';

// Mock the module that exports the singleton 'db'

vi.mock('@/lib/db', async () => {

// 1. Create a fresh in-memory Postgres instance

const client = new PGlite();

// 2. Connect Drizzle

const db = drizzle(client);

// 3. Apply Schema (using Drizzle's push or migrate)

// Note: PGlite is fast enough to run migrations per test file

await migrate(db, { migrationsFolder: './drizzle' });

return { db };

});

6.3 The “Memory Filesystem” Mechanism

PGlite can persist data to a virtual filesystem in memory (memory://). This means that when the test file finishes and the worker process terminates, the memory is reclaimed, and the database effectively vanishes. There is no cleanup required—no DROP DATABASE or TRUNCATE calls are needed. This “fire and forget” model drastically simplifies the test lifecycle.

6.4 Handling Server Actions with PGlite

Since Next.js Server Actions are just functions imported into the test, they will transparently use the mocked db module. When myServerAction() calls db.insert(...), it is inserting into the local PGlite instance running in the test thread. Because each test thread has its own mocked instance, they can run fully in parallel without any risk of data collision.

6.5 Performance Benchmarks

Comparative benchmarks reveal the efficiency of this approach:

- Startup Time: PGlite starts in ~20ms vs Testcontainers ~1500ms.

- Throughput: In a suite of 100 test files, PGlite allows running as many workers as CPU cores (e.g., 8 or 16). Testcontainers might be limited to 2-3 concurrent containers before saturating RAM.

- Execution: CRUD operations in PGlite are slightly slower than native Postgres due to WASM overhead, but the elimination of network latency (localhost TCP loopback) often compensates for this in integration test scenarios.

6.6 Pros and Cons

| Feature | Analysis |

|---|---|

| Speed | Very High. Instant startup enables a “Database per Test File” strategy. |

| Isolation | Perfect. Every test file gets a completely independent, shared-nothing database instance. |

| Parallelism | Excellent. Scaling is limited only by CPU cores, not RAM or Docker limits. |

| Compatibility | High. Supports most Postgres features (JSONB, Triggers). However, as a WASM build, it is single-process (no multi-connection testing) and may lack support for specific native extensions like PostGIS unless custom-built. |

| Dev Experience | Superior. No need to install Docker. npm install is all that is needed to run the test suite. |

Verdict: For 95% of Next.js applications using Drizzle, PGlite is the optimal strategy. It provides the best balance of speed, isolation, and developer experience.

7. Data Management: Seeding and Determinism

Regardless of the isolation strategy chosen, integration tests require data. “Seeding” is the process of populating the database with the necessary state (users, organisations, items) before a test runs.

7.1 The Drizzle Seed Library

The Drizzle team recently introduced drizzle-seed, a library designed to solve the problem of generating realistic, relational data. Unlike traditional faker libraries which are purely random, drizzle-seed uses a seedable pseudo-random number generator (pRNG).

Why Determinism Matters:

In testing, you want randomness to cover edge cases, but you also want reproducibility. If a test fails because a random name contained an emoji that broke your validation, you need to be able to reproduce that exact failure. drizzle-seed allows you to set a specific seed (e.g., seed: 12345). Every time the test runs with that seed, it generates the exact same set of “random” data.

7.2 Relational Integrity

Generating data for relational databases is hard because of foreign keys. You can’t create a Post without a User. drizzle-seed introspects your Drizzle schema relationships.

await seed(db, schema, { count: 10 }).refine((funcs) => ({

users: {

count: 5,

columns: {

email: funcs.email(), // deterministic emails

}

},

posts: {

count: 10, // Distributed among the 5 users

}

}));

This automatically handles the foreign key dependency, ensuring that every post created is linked to a valid user ID from the users generation step.

7.3 Factories vs. Global Seeds

-

Global Seeding: Populating the DB with a massive set of “standard” data at the start of the suite. This is good for read-heavy tests but bad for isolation (tests share the seed state).

-

Factories (Recommended): Using helper functions within each test to create only the data needed for that specific test.

// test/factories.ts

export const createUser = async (overrides = {}) => {

return await db.insert(users).values({

...defaultData,

...overrides

}).returning();

};

Combined with PGlite, this is extremely fast. Since the DB is empty at the start of the test file, the test creates 1 user, asserts against it, and finishes.

8. Comparative Analysis & Decision Matrix

To guide the selection of the appropriate strategy, we synthesise the findings into a decision matrix.

| Criterion | Transactional Rollback | Database Truncation | Testcontainers | PGlite (WASM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Quality | Medium (Connection sharing risks) | High (If serial) / Low (If parallel) | High (Process Isolation) | High (Memory Isolation) |

| Parallelism | Low (Difficult to implement) | None (Must be Serial) | Medium (Resource constraints) | High (CPU bound) |

| Startup Overhead | Fast | Fast | Slow (Docker spin-up) | Instant |

| CI Infrastructure | Minimal | Minimal | Heavy (Needs Docker) | Minimal (Node only) |

| Production Parity | High | High | Exact | High (High fidelity simulation) |

| Implementation | Complex (Proxies/ALS) | Simple | Moderate | Moderate (Mocking) |

8.1 Recommendations

For New (Greenfield) Next.js Applications

Adopt the PGlite Strategy. The benefits of parallel execution and instant startup significantly outweigh the minor complexity of setting up the mock. It allows your test suite to grow to thousands of tests without slowing down your CI pipeline. It aligns perfectly with the isolated module structure of Next.js Server Actions.

For Applications with Specific Postgres Extensions (e.g., PostGIS)

Use Testcontainers. PGlite currently has limited support for complex C-based extensions. If your app relies heavily on geospatial queries or vector similarity search (pgvector), the fidelity of a real Dockerised Postgres instance is non-negotiable. To mitigate the slowness, consider sharding your tests in CI (running different test files on different machines).

For Legacy Applications or Small Suites

Use Database Truncation. If you already have a working Postgres setup and your test suite takes less than 2 minutes to run serially, the effort to migrate to PGlite may not yield immediate ROI. Truncation is simple, reliable, and “good enough” for small scales.

Avoid Transactional Rollbacks in Next.js

The impedance mismatch between the “Stateless Request” model of Next.js Server Actions and the “Stateful Connection” model of SQL transactions makes this strategy brittle. It typically leads to “magic” code (Proxies, ALS) that is hard to debug and hard to onboard new developers to.

9. Conclusion

The landscape of integration testing in the Next.js and Drizzle ecosystem has shifted from managing shared resources to provisioning ephemeral ones. The “old way” of managing a single database and carefully cleaning it up is being superseded by the “new way” of creating disposables.

Technological advancements—specifically containerisation and WebAssembly—have given us new tools. Testcontainers allows us to treat a database server as an ephemeral object, while PGlite allows us to treat the entire database concept as a disposable JavaScript variable.

For the modern Next.js developer, the PGlite approach represents a sweet spot. It respects the boundaries of the framework, enables the blazing speed of Drizzle’s query generation, and provides the isolation necessary to banish flaky tests forever. By combining Vitest’s threading, PGlite’s in-memory speed, and Drizzle’s schema management, teams can build test suites that are not just safety nets, but accelerators of development velocity.

References

- Next.js and Drizzle Integration

- PGlite Architecture and Benchmarks

- Testcontainers Usage and Comparison

- Truncation and Seeding Logic

- Transaction Management in Drizzle

- Server-Only Constraints in Next.js